Fundamental Corrosion Challenges in Sternal Implants

Corrosion Behavior of Stainless Steels, Cobalt-Chromium Alloys, and Titanium Alloys in Biomedical Implants

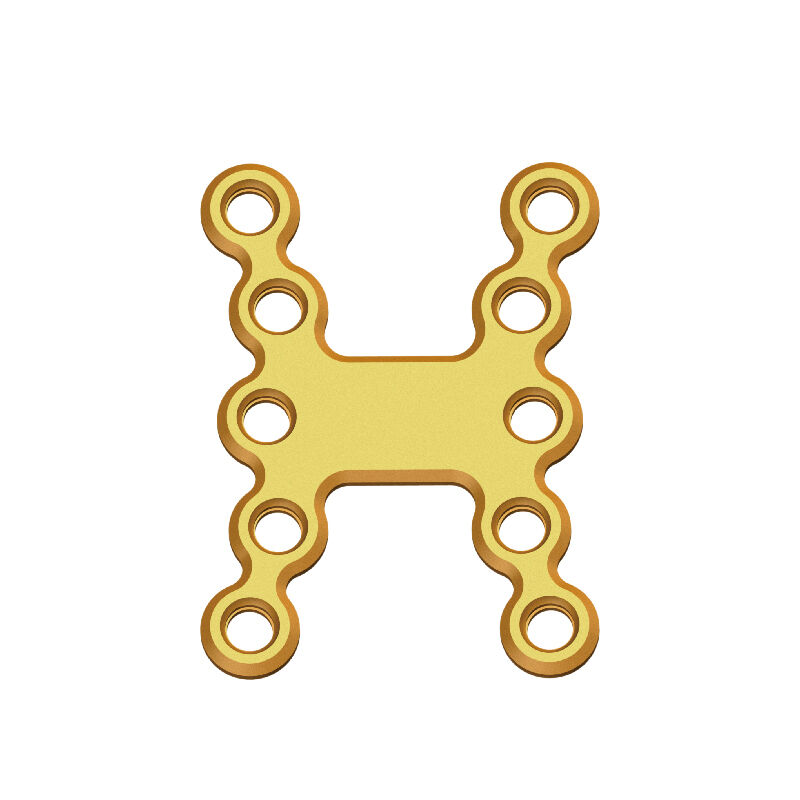

The main materials for making sternal plates include stainless steel, cobalt chromium (CoCr), and various titanium alloys. However, these materials behave quite differently when exposed to the corrosive environment inside the human body. Stainless steel might seem like a good choice because it's cheaper, but there's a problem. When body fluids rich in chloride come into contact with stainless steel, it starts developing those pesky pits much quicker than titanium does according to ASTM F2129 tests, about 12 to 30 percent faster actually. Cobalt chromium alloys handle crevice corrosion better, which is great, except they sometimes let out cobalt ions. Some studies show around half a percent to two percent of people who get implants made from CoCr end up with metallosis after ten years or so. Titanium stands out though. Its natural TiO2 oxide layer really works wonders, cutting down ionic leaching by almost 90% compared to stainless steel in lab simulations of bodily fluids. That makes titanium the clear winner when it comes to resisting corrosion.

Electrochemical Stability of Metallic Biomaterials in Body Fluid Environments

Inside the human body we find an extremely corrosive electrochemical setting because of those constant pH changes between 4.5 and 7.4 plus all that chloride floating around at about 113 mmol per liter. These conditions really kickstart both galvanic and localized corrosion processes. When it comes to passivated titanium though, things look better. The material keeps corrosion current densities under 0.1 microamps per square centimeter when tested in simulated blood plasma. That's actually about 40 percent less than what happens with Cobalt-Chrome alloys in the same situation. Stainless steel has different problems altogether. It depends on that protective iron chromium oxide coating, but this protection breaks down in areas where there's not enough oxygen near implants. Tests using cyclic polarization show these breakdown potentials can drop as low as 250 millivolts in serum solutions. And this means devices made from stainless steel face much higher chances of failing sooner rather than later.

Titanium Passivation and Its Role in Natural Corrosion Resistance

When titanium comes into contact with air or body fluids, it naturally creates a protective oxide coating around 4 to 6 nanometers thick right away. This thin layer of TiO2 acts as a shield against corrosion. What makes it really special is how resistant it is to electrical charges passing through – we're talking about resistance levels over a million ohms per square centimeter. That's actually three hundred times better than what we see with regular stainless steel. Some medical treatments can take this protection even further by using anodization techniques which build up the oxide layer to as much as 200 nanometers thick. Tests show these treated surfaces resist pitting damage about 73% better when subjected to physical stress. But there's one big catch: during surgery when implants are placed, the tools used can actually scratch or damage this protective film. Surgeons need to be extra careful with their instruments to maintain the material's longevity once inside the body.

Material Selection for Optimal Sternal Plates Corrosion Resistance

Biocompatible Metals for Orthopedic and Dental Implants: Titanium vs. Cobalt-Chromium vs. Stainless Steel

Titanium alloys are still considered the best choice for sternal plates because they resist corrosion really well and work great with body tissues, thanks to that protective oxide layer they form naturally. When looking at CoCr alloys, tests show they release about 32 percent fewer ions compared to regular 316L stainless steel according to those ASTM F2129 standards. However there's a catch here too since these materials have such a high stiffness level that can actually cause problems with bone healing around the chest area. Stainless steel might be cheaper option for short term fixes, no doubt about that, but without some special coatings or treatments on its surface, it just cant match up to titaniums impressive 88% protection against rusting over time especially when exposed to salt water like conditions found inside the human body.

Corrosion Resistance in Biodegradable Magnesium Alloys for Orthopedic Implants: Potential and Limitations

Magnesium alloys offer what many see as a good biodegradable option for implants, since they don't require removal after healing. But there's a catch. These materials degrade pretty fast, sometimes losing around 2.5 mm per year when placed in PBS solutions. That quick breakdown causes problems with maintaining structural integrity and also creates hydrogen gas as a byproduct. Some recent advances though are showing promise. High purity versions of Mg-Zn-Ca alloys seem to cut down on that gas production by almost half. When combined with special coatings made from hydroxyapatite and PCL polymers, these implants can stay functional for about 12 to 18 months. While this works well enough for children who need shorter recovery times, adults recovering from sternum surgery typically need implants that last longer, usually somewhere between 18 and 24 months according to standard medical practices.

Advanced Surface Modifications to Enhance Corrosion Resistance

Surface Treatments and Coatings to Enhance Corrosion Resistance in Sternal Plates

The way we engineer surfaces makes a big difference in how well metal implants perform electrochemically. When doctors talk about things like anodizing, plasma spraying or ion implantation, they're basically changing what happens on the surface of those sternal plates. This helps them resist corrosion better and last longer inside the body. Some tests show these surface treatments actually boost how long devices work properly by around 30% under lab conditions that mimic what's happening inside humans. The trick works especially well with metals such as titanium and cobalt chrome alloys because it strengthens their natural protective qualities against chemical reactions.

Plasma Spraying, Anodization, and Ion Implantation as Surface Modification Techniques

- Plasma spraying deposits micron-thick ceramic coatings, such as hydroxyapatite, to create a barrier between the metal and body fluids

- Anodization electrochemically thickens titanium’s native oxide layer, enhancing its dielectric and corrosion-resistant properties

- Ion implantation introduces nitrogen or oxygen ions into the subsurface, forming hard, chemically inert phases that resist breakdown

Nanocoatings and Their Impact on Long-Term Electrochemical Stability

Nanoscale coatings (<100 nm) made from ceramics or polymers offer superior protection, demonstrating 50% greater resistance to pitting corrosion than conventional coatings under ASTM F2129 testing. Their dense microstructure minimizes defects and microcracks, maintaining integrity during repetitive biomechanical loading while allowing controlled ion exchange essential for osseointegration.

Durability of Thin-Film Coatings Under Mechanical Stress: Addressing Clinical Concerns

Thin film coatings offer protection but they still struggle with peeling issues when screws are inserted or during normal rib movements. Recent advances though have made things better. Some new designs feature layered structures that gradually change properties, while others incorporate special healing materials that kick in when exposed to calcium from bodily fluids. These improvements seem to cut down on failures by about 22% for implants that need to support weight. Doctors were worried about how reliable these coatings would be over time, especially since patients expect implants to last many years without problems.

Standardized Testing and Compliance for Long-Term Performance

Implantable Metal Corrosion Testing According to ASTM F2129 Standards

ASTM F2129 serves as a detailed guideline when evaluating how well implanted metals resist corrosion, particularly for things like sternum plates and screws used in heart surgeries. The testing methods include cyclic polarization tests, potentiostatic holds, and scratch assessments that basically fast forward years worth of body wear and tear into just days in the lab. When it comes to titanium implants meant for the heart specifically, there's a strict requirement they must meet: corrosion current density needs to stay under 0.15 microamps per square centimeter. This threshold is crucial because it keeps the protective oxide layer intact, even when facing harsh environments inside the body where inflammation or acidity might otherwise break down the metal over time.

Simulating Body Fluid Corrosion in Laboratory Environments

Most manufacturers rely on body-like solutions for testing materials. These include things like modified Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) and phosphate buffered saline (PBS), kept warm at around 37 degrees Celsius to mimic real conditions inside the body where corrosion happens naturally. The main goal here is measuring how much metal gets released into these solutions. Cobalt chromium alloys tend to let out between 2 to 7 parts per million of metal ions each year when exposed to environments rich in chloride. That kind of release rate has been linked to possible reactions in surrounding soft tissues according to recent studies. Newer testing approaches now bring in movement elements too, subjecting coatings to repeated stress similar to what they'd experience during millions of breathing motions over time. Industry standards have shown these established testing procedures can predict actual body performance with roughly 92% accuracy when compared to results seen after five years of clinical use in patients.

FAQ Section

What are the common materials used for sternal implants?

The common materials used for sternal implants include stainless steel, cobalt chromium alloys, and titanium alloys.

Why is titanium considered superior for sternal implants?

Titanium is considered superior due to its excellent corrosion resistance, biocompatibility, and the natural protective oxide layer it forms which minimizes ionic leaching.

What are the limitations of biodegradable magnesium alloys?

Biodegradable magnesium alloys degrade quickly, potentially losing structural integrity, and produce hydrogen gas as a byproduct.

Table of Contents

- Fundamental Corrosion Challenges in Sternal Implants

- Material Selection for Optimal Sternal Plates Corrosion Resistance

-

Advanced Surface Modifications to Enhance Corrosion Resistance

- Surface Treatments and Coatings to Enhance Corrosion Resistance in Sternal Plates

- Plasma Spraying, Anodization, and Ion Implantation as Surface Modification Techniques

- Nanocoatings and Their Impact on Long-Term Electrochemical Stability

- Durability of Thin-Film Coatings Under Mechanical Stress: Addressing Clinical Concerns

- Standardized Testing and Compliance for Long-Term Performance

- FAQ Section

EN

EN

FR

FR

ES

ES

AR

AR